The story of my journey with this play is similar to that of its protagonist, Lowell Carpenter, in ways that still surprise me.

The story of my journey with this play is similar to that of its protagonist, Lowell Carpenter, in ways that still surprise me.

Like Lowell, the story begins an article in the New Yorker (not the New York Times). The play I wrote is inspired by real life events that were discussed in that article. A real individual (a prosthetics device specialist), embarked on a worthy project and somehow, it all went wrong. I was to learn this situation frequently occurs with humanitarian projects.

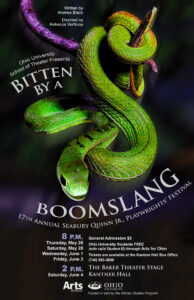

I thought the idea of a project with noble intentions that falls apart was worth exploring. I got the idea while in graduate school and have told friends that this play was the one I went to graduate school to write. I cannot imagine that I would have been able to write a play of this scope without support and encouragement. It takes place on two continents, two of the leading characters are African amputees and, among them (in the original drafts), the characters spoke four different languages. At that early stage in my writing career, I don’t think I would have had confidence in my ability to craft such a story for the stage.

Learning to write a play in graduate school, however, is like learning to ride a bicycle with training wheels. I knew I was free to take risks. Ohio University had an African Studies department. The year I wrote the play, I was able to take a seminar from a visiting professor on “Gender, Culture and Identity in African Literature.” There were plenty of resources to support me. I had to do a great deal of research. Not only did I know very little about Sierra Leone, a key location in the play, but I knew very little about Africa in general. I also knew very little about prosthetic technology. There was a lot to learn.

The play was well received and in my second year, it was produced in the Seabury Quinn Jr. Playwrights’ Festival at Ohio University. That summer, I went to Africa as part of a study abroad program to learn more about African art and music. I studied in Ghana. While there, I was fortunate to have an opportunity to have the play read at the National Theatre of Ghana, by actors from their company. It was a wonderful experience, funny and lively, and the response let me know I was on the right track, although the presence of gay characters in my play threw these actors a bit of a curve. I know the actor who read the leading part had never played a gay character before and probably never will again.

Following my three weeks in Ghana, I made a one-week side trip to Sierra Leone, a country that few Americans ever visit. My intention was to do artistic research while there. I wanted to visit refugee camps, meet with NGO’s and find out more specifically about the music of Sierra Leone.

My play is about a man (Lowell) who wants to do a humanitarian project in a country whose culture he does not understand: I am a man who wanted to do artistic research in a country whose culture I did not understand. Both of our projects were/are doomed to a certain kind of failure. Given the logistical constraints, I found it quite hard to lay the kind of groundwork for my trip that I would usually put in place. Not only that, but many of the elements I thought I had set up did not materialize as I expected them to. It turned out, I had made arrangements to stay in what I would now call the “wrong part of Freetown” and I was quite isolated and had a hard time getting around. I was able to accomplish some of my tasks. Meeting with actual refugees in the camps, however, turned out to be surreal. You can’t really make appointments, and the face-to-face meetings with these men and boys who had lost their arms and legs were almost more than I could handle. It was clear that very few white men from America ever made the kind of trip I was making; they were not sure what to make of me. It was a fact of my experience that many people seemed to be trying to figure out how they could take advantage of what they believed (somewhat inaccurately) to be my wealth. I found it difficult to know what to do with that. The needs of the people I met were so great, it was easy to be somewhat destabilized psychologically. I left Sierra Leone with a greater appreciation for Lowell’s journey as a character than I did for Sierra Leonean art and music. I probably got what I needed, though not in the way I expected to.

I am very proud of this play, which as of this writing, is still looking for its first professional production. The story of a man who has a noble vision that, in some ways, blinds him to his own motives is very close to my heart. You could say that I too have been Bitten by a Boomslang.