I have always loved Agatha Christie. I have a memory of reading (and loving) her classic And Then There Were None when I was in the fifth grade. Little did I know at the time I would be using that book as the inspiration for a full-length play later in my life.

I have always loved Agatha Christie. I have a memory of reading (and loving) her classic And Then There Were None when I was in the fifth grade. Little did I know at the time I would be using that book as the inspiration for a full-length play later in my life.

I will say that my love affair for Agatha Christie as a writer waned as the years went by. The things that a 10-year-old boy responds to are not the same as the things that a mature adult responds to. The plots of Christie’s mysteries are often predictable and wooden. With a few exceptions, if you’ve read one or two, you’ve read them all. However, Agatha Christie is to this day one of the most-produced playwrights in the United States. Her brand is incredibly strong and audiences love, love, love the murder mystery formula. All this aside from the fact that Agatha Christie is not really a very good playwright. Of course, her mystery, The Mousetrap, has been in continuous production in London since 1952; I should be so lucky to be that bad. Christie’s book, And Then There Were None (ATTWN) was likewise turned into a play (and several movies), though the story was rather significantly re-imagined for the stage.

One of the things that originally inspired me as a playwright was the idea of taking existing properties with heterosexual characters and re-conceiving them for gay characters. Since my beloved writing partner Patricia Milton and I had successfully realized this vision with two other plays Porn Yesterday and Strange Bedfellows, tackling a murder mystery as our next project made sense to us. In this endeavor, we had the support and encouragement of Ed Decker, the artistic director of the New Conservatory Theater in San Francisco. He himself had a vision of a murder mystery with gay male characters following the contours of And Then There Were None. When he saw a staged reading of one of our early drafts, he extended to us a commission for the completion of the work. It was our first commission and we were in business.

One of the issues with murder mysteries is the identity of the hero or protagonist. In the classic murder mystery, the detective (think Hercule Poirot) is usually a character outside the central action of the play, which means that while the major dramatic question is his (or hers), that character usually has little investment in the outcome. If the “detective” is one of the characters involved in the play, the challenge is to make that character really interesting. One of the dramatic problems with the stage version of ATTWN is that the protagonists are the least interesting people on stage. The male and female characters who survive the series of murders are dull and insipid. All the really interesting characters have been killed off…..not a satisfying conclusion.

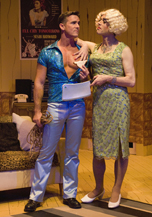

As we developed our play, we realized that our “old queen” stereotypical character was actually one of the most fun in the show. We elected to develop him as the protagonist and to balance him off against a young gay millennial. Our play, instead of featuring a man and a woman who must overcome their natural mistrust of each other’s gender, features two characters who must overcome their natural mistrust of each other’s generation. Thus, we were able to layer in a message about ageism in the gay community. We were also able to create two dynamic, interesting protagonists the audience could relate to and root for.

I think of this play as “Agatha Christie meets Paul Rudnick”. We had an incredible amount of fun with it and it was the first time one of our plays had actually been produced in the city we lived in, so we were able to be involved with the production in ways that were very satisfying. We owe Ed Decker a lot for working with us on this production and the director and all the cast members certainly brought their a-game to the production.

In this (and in subsequent productions), no blood has been spilled, no tears have been shed, and a lot of fun has been had by all. To mis-quote our own title, “It hasn’t been murder, Mary!”